Geyikbayiri in Turkey is a place I always assumed I’d visit. I’d heard about the fabulous rock formations and the hundreds of quality lines. But given I try to avoid flying in order to keep my carbon footprint down, and given it’s quite a long way from my home in London, it had been consigned to the pile of “one day, as part of some epic trip, when I have unlimited time and freedom”.

So when Glyn Hudson phoned me up, excitedly proposing that we go there, I was initially a bit sceptical. There are many great climbing areas much closer to home, but Glyn had won a competition to get a place on the Petzl Roctrip, which was to travel through eastern Europe, finishing in Turkey. Glyn’s prize was to be flown out there for a week. But having a similar desire to avoid flying, he wondered about making the journey overland. Friends who are willing to undertake multi-day overland adventures to reach a destination equally accessible via a quick hop on a short-haul flight are few and far between, and Glyn’s list of such people contained only one person: me.

I agreed, of course. I knew it would be an epic adventure and a chance that wouldn’t come along again in a hurry. So I accepted that my time to visit Turkey had now come.

The plan emerges: Turkey via land and sea, with a week’s stop in Athens

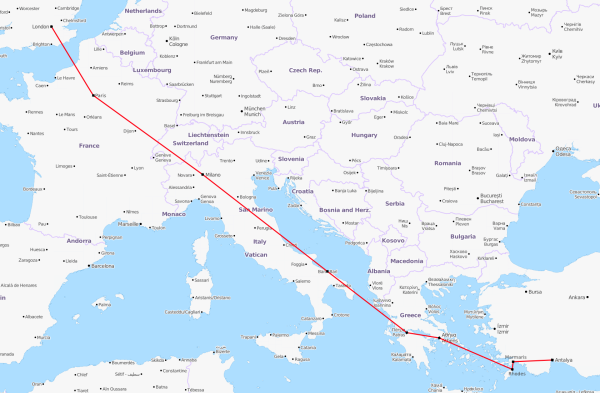

There are basically two ways to reach Turkey overland by public transport.

The first involves pure train travel through Germany, on into eastern Europe, and finally on to Istanbul (visit The Man in Seat 61 for all the gorey details). Once in Istanbul, we’d need to undertake an overnight coach journey to get to the south of the country where Geyikbayiri is located.

The second route takes trains to Bari in southern Italy, and then ferries directly to the south of Turkey using Greece and its islands as stepping stones.

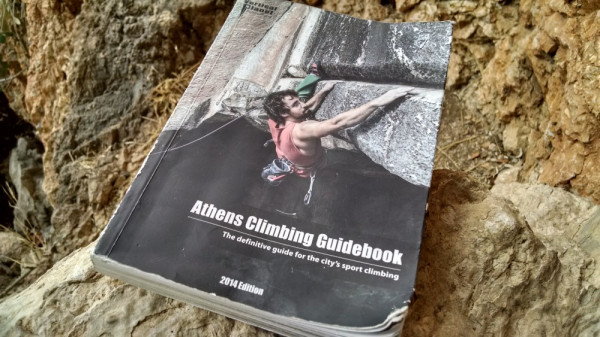

Either way involves at least 4 full days of travel, so we were keen to find a way to break the journey up a bit. I’d heard about the new Athens Climbing Guidebook, published only this year. Athens is surrounded by loads of quality crags, but has remained relatively unknown in the international climbing community, in part due to the absence of a comprehensive English-language guidebook.

Local climbers Antonis, Andreas and Giorgos set out to change this, launching a crowd-funding campaign to finance their work. They did an outstanding job and have produced a comprehensive, clear and useful book, packed with fantastic photos and an individual description for each and every route.

We went to have a look!

Overland to Athens in 3 days, 2 nights

The journey came off without a hitch. One thing I love about overland transport is that the transition from Home to Away comes slowly and gradually. Rather than being violently shoved from one city, culture and climate to another you ease into the trip. You arrive with a feeling of achievement and excitement rather than with an abrupt jolt, stepping sleepily off the plane into another soulless airport.

We took a morning Eurostar to Paris, where we had a bit of time to walk around in the sun and sample the wares from a boulangerie.

After lunch we boarded a TGV to Milan, and upon checking in to our hostel adjacent to Milano Centrale station, we sampled a local bar before getting some sleep.

An early train the next morning took us down the western side of Italy to Bari, where we dawdled through the cobbled streets of the old town, took a dip in the warm ocean, and enjoyed a hand made pizza in a wood-fired oven.

In the evening we boarded our boat to Patras, on the Western side of Greece.

It was a long one so we enjoyed a long sleep and a lazy breakfast the following morning, sunning ourselves on deck as we glided past Greek coastline and scattered islands.

Arriving around 1 PM, we shared a taxi to the town centre and boarded a coach to Kiato. In Kiato it was a short interchange onto a modern suburban railway taking us into Athens itself.

After picking up a hire car (fairly essential for Athens climbing, as the crags are dotted around) we checked into a campsite in Kifissia on the outskirks of the city. This turned out to be a good choice – the site was green and leafy with wifi and hot showers. It was close enough to the highway that we could get around easily, but not so close that we had to listen to traffic noise all night.

Mavrosouvola: a huge cavern with tufa dreadlocks

Looking at the guidebook, the crag which had stood out to us particularly strongly was the giant cavern of Mavrosouvola. Not having much in the way of tufa climbing back in the UK, we are drawn to these magnificent formations.

It did not disappoint and we lapped up the easier routes to try to build up some fitness for the rest of the trip.

Unusual climbing on an ancient marble quarry

The following day we sampled something a bit more unusual. It had never occurred to me that a marble crag might be a thing that existed. But if it does exist, of course it must be in Greece! In fact, Spilia Daveli is an ancient marble quarry which is said to have supplied stone for the building of the Acropoplis. And you can climb there!

The brilliant white rock certainly gives a unique experience. Onsighting is particularly hard because the holds are not particularly easy to spot, and any chalk left over from previous ascents blends in easily. That said, Glyn did some great onsights which I managed to flash thanks to his beta.

Unfortunately for us, not all of the routes are fully bolted. As we didn’t have any trad gear with us on the trip, we had to give these ones a miss.

Glyn onsighting Gerakina 7b+ at Damari, which is round the corner from the main Spilia Daveli crag

More immaculate tufa climbing at Vrachokipos

The following Sunday we were able to meet some locals, including Giorgos and Andreas who worked on the guidebook, at another great crag named Vrachokipos. This was a welcome change as we had spent the week climbing on our own, but today the crag was packed with friendly people; beta and route recommendations came thick and fast.

A project emerges

For better or for worse, I had involved myself with a serious project at Mavrosouvala in the previous days. Aintes, if I could achieve it, would be my first route at 8a. I’d got to the “obsession” stage of redpointing and so I tried to take it fairly easy at Vrachokipos in order to conserve energy for some final attempts the following day. It was my last chance as we’d resume our journey to Turkey that night.

Usually when redpointing, I know when I’m about to be successful. Everything just comes together and it seems like victory is inevitable. I had this feeling while in an awkward knee-bar rest prior to the last hard section. I knew I’d do it this time. I was sure. But I was wrong: the moment I left the rest, I felt my muscles collapsing. As I desperately stabbed into the finger pocket I knew it was over and I left empty handed.

I don’t regret trying, it was a beautiful route, long and hard. I remember watching a video from Dave McLoed some time ago, where he said that if you know for sure that you’ll be able to achieve something you’re not really pushing yourself. Failure is part of the process, it provides verification that you’re really trying hard. In the end I “knew” I’d succeed, but actually I failed. I’m not sure what that means per McLoed’s rules but I was definitely trying hard!

One downside of having this project is there were quite a few crags around Athens which we didn’t make it to. There were quite a few other places which looked really good in the guidebook, so I’d be psyched to go back some time and check them out.

Onwards to Turkey

There are no direct ferries from Greece to Turkey, so it was with a deep sigh of resignation that we accepted we’d probably need to spend a day on one of Greece’s sun-baked islands in the Mediterranean. Perhaps we’d engage in a bit of swimming, purely as a form of “active rest” of course. And perhaps sample the local cuisine, strictly for research purposes, naturally.

There are a few possibilities but the route we chose took an overnight ferry to Rhodes, which is pretty close to Turkey. After a day out in Rhodes we then took an hour’s ferry ride to Marmaris in the early evening. We then had about a 5 hour drive in a hire car to Geyikbayiri.

Another possibility would have been to stop on the island of Kos and then take an onward ferry to Bodrum. Bodrum is further from Geyikbayiri, but from there it’s possible to take an overnight bus to Antalya if you wish to arrive purely by public transport.

Geyikbayiri: too hot, but amazing rock

We got to Geyikbayiri early in October and settled in to the JoSiTo campsite, which was friendly and well-equipped. Despite being “in the mountains” to some degree, the weather was much hotter than we’d experienced in Athens, so it was necessary to climb in the shade. This meant that we only visited the north-facing crag of Trebanna. It’s certainly a great crag and we had plenty to go at, but we’d have liked to have been able to check out some of the other crags too. It also suffers from being the rainy-day and hot-day option, so there’s a fair bit of polish from all the traffic.

I’ve never seen rock like they have in Geyikbayiri. Some places have tufas, but this place has giant columns of rock which you can walk around. It often makes for very three dimensional, pumpy climbing.

The Roctrip arrives

The Petzl Roctrip arrived in Geyikbayiri a few days after us. Immediately the crag became significantly more crowded and hectic. Uber-wads cranking on the sharp end of bright orange Petzl ropes became a common sight!

Daila Ojeda with a shiny Petzl rope. I tried to practise my Spanish with her which wasn’t wildly successful. She did teach me the word for “battery” though (la pila) – thanks Daila!

Up-and-coming hard climbing at Citdibi

One nearby crag that the Roctrip was trying to draw attention to is Citdibi, about a 45 minute drive from Geyikbayiri. This was a welcome change from Trebanna, and an incredibly impressive wall.

Citdibi has a lot going for it. Being much higher in the mountains than Geyikbayiri, it has cooler conditions. The huge wall overhangs quite a bit, so even though it rained pretty hard while we were there, the rock we were climbing was bone dry.

On the downside, it’s a fairly new area so there was still a fair bit of loose rock and dustiness. That’ll clean up in time, it just needs more people to climb there.

The other problem I experienced is that the climbing is really quite hard. All the best-looking lines were 8a and upwards. They did look amazing, but too hard for me to have a casual go. Obviously this “problem” depends on how hard you climb, but I found it a bit frustrating that all the really good lines seemed too hard for me.

There’s loads of potential for development at Citdibi, which I’m sure will happen over the coming years, so if you’re in the area I’d recommend a visit.

Walking up to Citdibi. We couldn’t find the proper path on first day here, but the forest was pretty nice.

The main “Kanyon” sector provides an incredible viewing platform which lets you spectate climbers when they’re about 30m up!

Onwards to Olympos

We moved with the Roctrip to the seaside venue of Olympos. It’s a funny place; my understanding is that during high summer it functions as a kind of hippy version of Magaluf. Visitors come in droves for sun, sea, sand and stupid quantities of alcohol. But there is some climbing too, leading to a slightly odd scenario where the tourist businesses try to cater for this secondary and quite different market too.

Initially we stayed in Kadir’s Tree Houses, as this was the chosen location of the Roctrip. This place is presumably so named because it sounds more quaint than “Kadir’s Wooden Shacks With Rusty Nails Poking Out the Walls”. Whereas in Magaluf you can presumably retreat from the nightclub to your lodgings once you’ve had enough (I’ve never actually been), the same cannot be said of Kadir’s. The loud music went on every night until about 3 AM, and because everything is made out of wood there was little respite in our room. Even my earplugs barely helped. Perhaps the loud music can be put down to the “Roctrip effect”, but judging by the reviews on Tripadvisor it’s par for the course here.

The climbing itself was rather good, though not plentiful enough that I’d ever want to return. I did some quality routes on the Cennet sector, which features face-climbing with pockets, a welcome antidote when we were becoming weary of tufas. I intended to try out some other crags including the Deep Water Soloing venue, but…

Then we were poisoned

One night we came back late and they had stopped serving dinner. We asked if they could possibly sort us out and a minute later two plates emerged from the kitchen. Relieved, we devoured our meals.

Several hours later as we lay in bed trying desperately to ignore the throbbing beats of the party, Glyn began to feel sick. Thus began an awful night of puking (for Glyn) and diarrhoea (for us both), and we spent the entire next day bedridden feeling totally weak. When I eventually managed to get up and have a shower, it felt so exhausted that I immediately had to lie down again.

I can’t conclusively draw a link between the food we had and the ensuing illness, but the correlation seems pretty suspicious. We’d had enough, so relocated ourselves to a place called Deep Green Bungalows, which was better in just about every way. It was cleaner and quieter, the food was better and the owner was friendly and eager to help.

Whilst after the second night of resting I began to feel a little better (though not perfect) and did a bit more climbing, Glyn was in bed literally until we left. It was a pretty rubbish end to an otherwise great trip. In the following days I spoke to lots of other people who had either felt ill themselves, or knew someone who was feeling ill; surely not a coincidence.

Back to London

When it was time to leave we were glad to do so. Despite our interesting and involved outbound journey, we’d decided due to time constraints to fly back. It felt like a bit of a cop-out for me, especially as I usually try to avoid flying anywhere, but I suppose the convenience won in this case. That said, arriving in Luton airport at 1 AM with our body clocks on 3 AM did not in any sense feel like a victory.

Food highlights

I don’t want to finish the post on a negative. Overall it was a great trip, despite the ending. So let’s talk about food!

I love sampling different food on climbing trips. Often it’s not the “national dishes” which bring the most pleasure but the simple joys such as eating succulent local oranges in Chulilla, or buying fresh croissants in France. Here are some of the tasty things we ate on this trip.

We couldn’t find gas for our stove in Athens, so we made amazing salads. In this instance, we also ate the bowl, which was made of bread and came from the local bakery!

Rest day veggie burger at Avocado Athens – one of the best I’ve ever had!

I spent the whole time in Athens trying to find a fig tree which actually had figs on it. One the last day I was finally successful, which was an intensely happy moment as you can see.

Gözleme is a kind of Turkish pancake snack, filled with meat, cheese, spinach, tahini, etc. It’s yummy.

Turkish tea being poured. Very much a national institution, this was available everywhere we went, always served in the same shaped glass cups.

Pingback: Sunshine and Sport Climbing in Athens | Rachel Slater